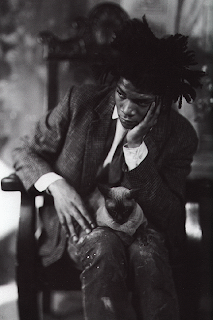

i enjoyed the almost-silhouettes from Katherine Wolkoff's series Nocturne when i first saw them (top). and i love this one as an actual silhouette on the cover of the new Vintage Classics edition of Jane Eyre coming out next week.

i'm fascinated by the practice of using fine art photography on book covers in general (is it wrong that i think it's sweet when art photos have a 'practical' 'use' too?), and this is a fantastic example, gleaned from the awesome Book Cover Archive.

Jane Eyre was published only eight years after the first daguerreotype portrait was taken in 1839.

as for the potential meanings of this particular cover photograph selection for this novel, it made me think of the book Fiction in the Age of Photography by (my former professor, the fabulous) Nancy Armstrong:

"The allurements of the fully exposed body necessarily canceled out both its maternity and its feminity, since these were private functions of the woman...While the respectable woman could be said 'to have' a female body, her relation to that body resembles what D.A. Miller calls 'the open secret.' Her identity as a feminine and maternal woman indicated that she had an erotic life which she had scrupulously withheld from public view. To grasp the extent to which this open secret shaped Victorian fiction, one need only recall how any one of Charlotte Brontë's heroines shrinks into corners and niches or fades into the background behind her more flamboyant rivals and companions. Jane Eyre, Lucy Snowe, and Caroline Helstone will do anything to avoid the limelight, and Brontë consequently allows us to see them only as they watch men watching other women make spectacles of themselves.

The two halves of the popular body--the feminine and the female--were indeed two halves of a single cultural formation. That construct was organized by a contradiction between the body which contained and concealed a woman's sexuality, on the one hand, and the body as manifestation of that sexuality, on the other. The feminine and the female could not coexist within a single photograph, since they ostensibly addressed entirely different audiences who looked at the body in entirely different ways."

and we'll give the last word to Ms. Brontë herself:

"Listen, then, Jane Eyre, to your sentence: to-morrow, place the glass before you, and draw in chalk your own picture faithfully; without softening one defect; omit no harsh line, smooth away no displeasing irregularity; write under it, 'Portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor, and plain.'"